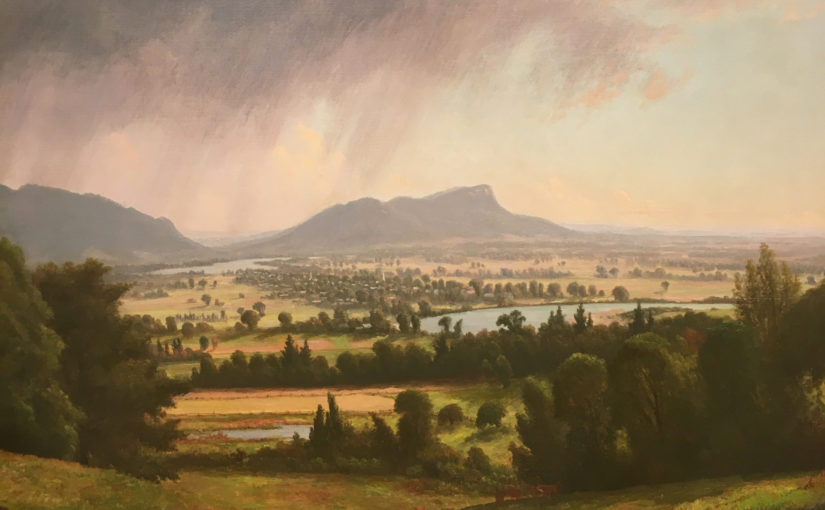

“The many historical uses and meanings of the Meadows have left their marks on the landscape. Today, what would a representation of the Meadows look like that pays generous attention to them? What mixtures of subject matter and means would inform them? What understanding and interpretation of the Meadows’ natural and cultural histories would shape them?” –The Great Meadow, 2016

These are the questions that Anthony Lee, Claudette Lambert Peterson and I addressed in our exhibition The Great Meadow: Natural and Cultural Histories of Northampton’s Meadow at Historic Northampton.

I wanted to look extremely closely at a landscape that has been so well documented already, using a robotic tripod to gather panoramic images of the smallest details of the ground. You see a lot of bugs and trash from an altitude of two inches, but also features that echo river bends and stone walls.

I especially enjoyed the creative process of working as a group to understand the Meadows, with Lee’s landscapes informing my choice of subject matter and the bits of trash I found making an appearance as natural history objects in Peterson’s work. Technology is ubiquitous in the “natural” setting of the Meadows, from the bottle caps and other human castings to the cultivated corn and bits of brick.

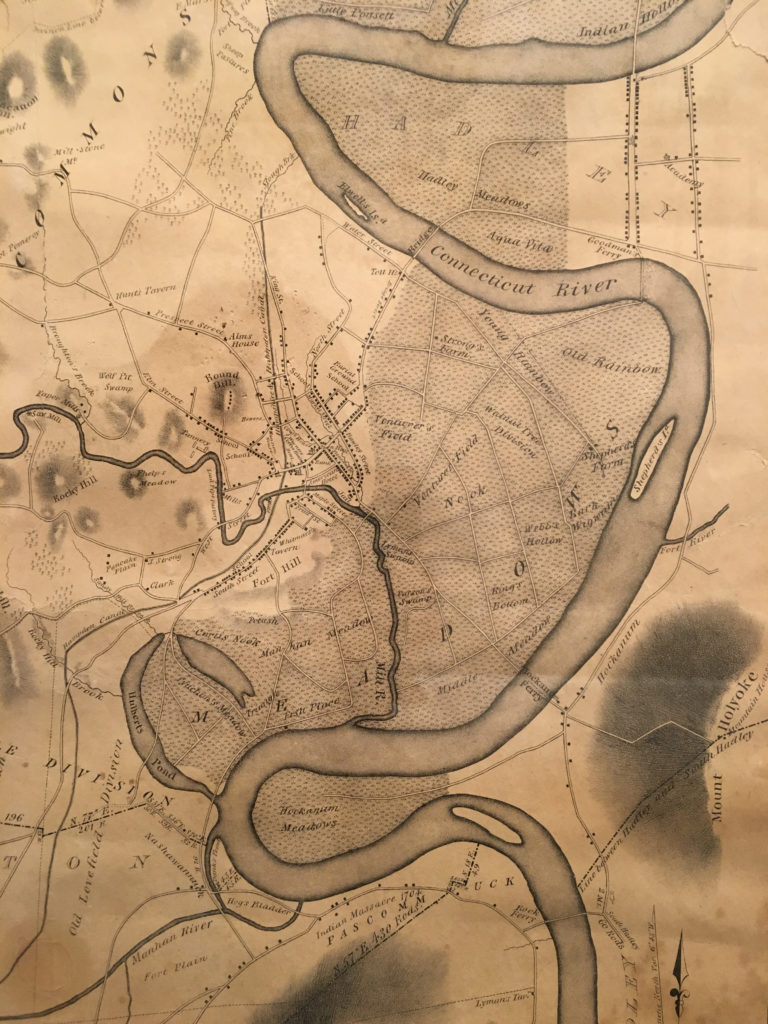

The names the 17th century settlers gave to plots of the Meadows are evocative. Venturer’s Field was so called because a family chose to spend a winter in a cave there. Bark Wigwam referenced an existing structure, but also the presence of other inhabitants. And you can easily imagine how Hog’s Bladder got its name. There is a ball field in the Meadows to this day.